…or on the margins of a world day

17 June is a day that reminds us every year that our home, the Earth, is facing water scarcity and desertification in more and more areas. Or the planet is not struggling, we are. And it is no longer a reminder of the world day, but of everyday reality.

Részletesebben a világnapról >>>>

1994. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) was adopted on 17 June 2009, making it World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought.

The aim of the World Day is to raise awareness of the need to protect soil quality, the link between desertification and migration, land degradation and dwindling food resources, among other issues.

For a long time, we only saw great dramas on TV. For the majority of us, floods, landslides, droughts, huge fires and so on are still only on the screen. They do not yet associate the phenomena with the rise in food prices in the shops or the interrupted water supply at night. Certainly not with your own habits.

What do you think? Is the solution still in our hands? Can we take it in our hands through real knowledge sharing, right now? Or should we wait for someone else?

John F. Kennedy said in his 1961 inaugural address that

“Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country!”

No, but let’s not get sentimental! The reality is that it is time for action, not waiting. And this is not the task of big politics, nor of distant decision-makers. This is our home, our community, our future.

Let’s face it, we can take the first, most important steps ourselves!

Let’s discover together how to protect the source of our life, water, in our own backyard, in our own kitchen, for our own family! Starting with the small steps, and then we’ll take it from there!

Let’s put our homes, our communities, our communities on the map of sustainability! In fact! Let’s be the first in the search engines!

It may even seem like going to the moon now. A big mission, indeed! But what did Neil Armstrong say when he stepped on the moon?

“It’s one small step for one person, but a giant leap for mankind.”

It is important to raise awareness that conscious water management and individual responsibility is not a renunciation, but a key to prosperity and a sustainable future. It would be a renunciation not to do so. Our future. The future of our children.

Together, let’s see how we can protect the source of our lives in our own homes!

Egy kicsit tudományosabban a háttérről elemző típusoknak >>>>

We don’t like a lot of talk either. But if you’re the analytical type and want to do a bit of tidying up of the huge amount of data we’re getting, we’ve done some background work for you.

- How much of the area is desert now?

- And how much is the threat of desertification?

- How much fresh water can be used?

- And doesn’t the melting of the ice mean more usable land?

Well, we try to answer these and similar questions below. At least on the basis of the scientific information we can find, which is often contradictory to the point where it seems as if someone has deliberately worded it in a way that makes it difficult to understand.

It just confuses us so much that we don’t feel ownership of the problem. Then the next day, of course, nature comes knocking again, with no comment.

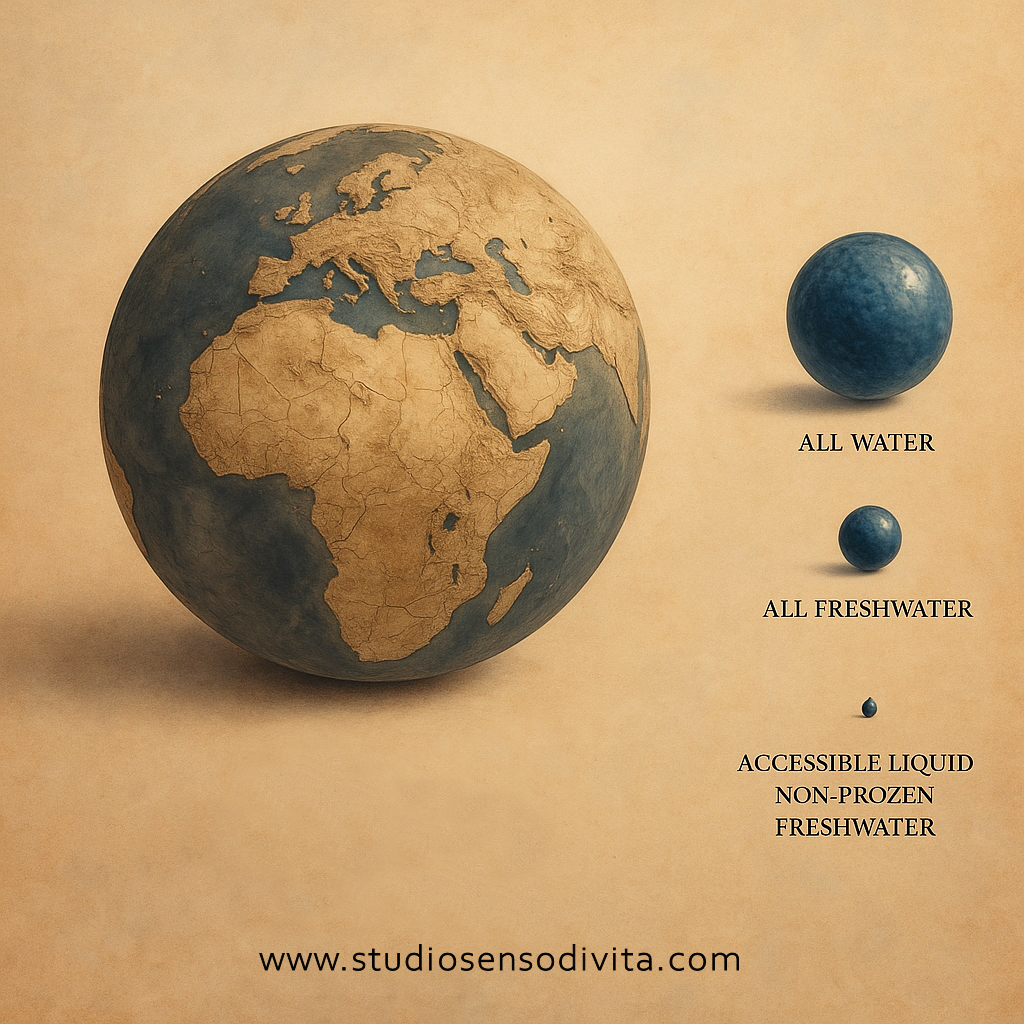

Water use has grown at twice the rate of the world’s population over the past century. At the same time, the Earth’s water supply is constant. And only 1% of all water is suitable for human consumption. And we only have access to a fraction of that.

It might be worth reading the above paragraph again…

It is from this “teaspoonful” that we grow our food crops, water our animals, produce our consumer goods, and use it for drinking, bathing, filling our swimming pools, watering golf courses, roads…

It’s hard to imagine when you’re standing by the sea…

With detailed data >>>

The volume of the Earth is about 1.08 trillion km³. The total volume of water compared to the Earth is about 1.386 billion km³. Of this water, the Earth’s total freshwater supply is only about 2.5%, but even most of this water is either locked up in ice (glaciers, Arctic ice caps) or deep underground (deep groundwater), which is not easily accessible or extremely expensive to extract (and in our opinion, not ethical.) So 1% is a rough figure for the amount of freshwater that can be used from that 2.5%.

However, the amount of liquid (non-ice-bound) freshwater directly and immediately accessible to humans is only about 0.007% of the Earth’s total water supply. This is a teaspoon-sized drop compared to a globe the size of the Earth.

If we want to visualise this and put all of the Earth’s water resources – salty and sweet – into a sphere (top blue sphere next to planet Earth in the image below), we can see the Earth-to-water ratio. The middle sphere shows the total freshwater supply (volume matters, don’t look at the plane!), and the small blue sphere at the bottom shows what freshwater is directly and immediately available to humanity from all of this:

Yes! That little dot at the bottom of the picture…

The figure is not perfect, of course, and the screen is not big enough to see the true scale.

The Earth’s freshwater resources are threatened not only by overconsumption, but also by climate change, environmental pollution, soil and water contamination, economic growth and changing lifestyles. Clean drinking water is already in short supply.

According to the UN, more than two billion people lack access to clean drinking water today, and by 2040 the demand for drinking water will be 30% higher than the available supply. At that sentence, it is perhaps worth rewinding to this paragraph…

Well, but let’s look further!

Desertification of the Earth’s land areas

Let’s take a point-by-point look at the distribution of the Earth’s land surface in terms of desertification, as clearly as possible.

1. The entire land surface of the Earth

This is the base we start from: the entire land area of the Earth, including both the ice-covered parts (e.g. Antarctica, Greenland) and those where there is no frost. This is considered 100% when we talk about land ratios.

2. The 100% ice-covered part

The Earth about 10-11% of its total land area (100%) is permanently covered in ice.

3. 100% of the already desertified part

The Earth about 10-14.35% of its total land area (100%) is already deserted . These are areas that have become virtually desert due to water scarcity and degradation.

4. 100% threatened (risk of further desertification)

The Earth about 26-30.75% of its total land area (100%) is at risk of desertification. These areas are not yet deserts, but they are seriously degraded and at high risk of desertification due to water scarcity and poor land use.

5. In summary: what percentage of 100% (including the already desert) could become desert?

This is the part where the two categories (already desertified + threatened) are added together to show the full extent of the problem on the Earth’s landmass:

- Lower estimate: 10% (already deserted) +26% (threatened)=36%

- Upper estimate: 14.35% (already deserted)+30.75% (threatened)=45.1%

So, around 36-45% of the Earth’s total land area is already affected by some form of desertification (i.e. already desertified or severely threatened).

6. For habitable land not covered by ice, this is

This point, as you have highlighted, is particularly important because it concerns the areas where humanity actually lives and farms!

- The Earth about 89-90% of its total land area (100%) the ice-free land where we live.

Now let’s look at what proportion of this 89-90% is the total area affected/threatened by desertification (i.e. 36-45%):

- Lower estimate: 36% (total affected)/90% (ice-free land)≈0.4=40%

- Upper estimate: 45.1% (total affected)/89% (ice-free land)≈0.5067≈50.7%

So, if we look at the land area that is not covered by ice, habitable and arable, around 40-51% of it is affected by desertification (already desertified or severely threatened). This is a dramatic figure that highlights the direct impact of the problem on human life and our natural resources.

Desertification and melting of ice-covered areas

The two processes, desertification and melting ice sheets, are effects of climate change, but they do not go hand in hand in such a way that one ‘compensates’ for the other.

- Does desertification go hand in hand with the melting of ice-covered areas?

- Not directly. Desertification occurs mainly in drylands and regions that are becoming drylands, where higher temperatures, changes in rainfall distribution and inappropriate land use lead to soil degradation.

- The melting of ice-covered areas is a direct consequence of global temperature rise (climate change). Although both are caused by climate change, desertification does not cause ice to melt, nor does melting solve desertification. In fact, melting glaciers and ice caps, while adding more water to systems in the short term, lead to long-term water shortages in regions that traditionally rely on glacial meltwater (e.g. the major rivers of Asia).

- Not directly. Desertification occurs mainly in drylands and regions that are becoming drylands, where higher temperatures, changes in rainfall distribution and inappropriate land use lead to soil degradation.

- How large is the area of land under the ice that could potentially become habitable, liveable land?

- This is a highly speculative question, but the scientific consensus is that this area will not be significant, and the resulting ‘new’ land will not be immediately or easily ‘habitable, liveable’.

- Much of the land beneath ice-covered areas, such as Antarctica and Greenland, is extremely inhospitable. Deformed under the pressure of thick ice, it is mountainous in many places and deep below sea level in others. The soil quality would be extremely poor and the climate would remain extremely harsh (extreme cold, strong winds) even after the melt.

- In addition, the melt would cause a massive rise in sea levels, which would submerge much of the Earth’s current, most densely populated coastal areas. So, even if all new ice-free land were created, it would be outweighed by orders of magnitude by the amount of farmland and urban land that would be submerged.

- Overall, then, there is no question of the melt creating “new habitable areas” to offset desertification or sea-level rise.

- This is a highly speculative question, but the scientific consensus is that this area will not be significant, and the resulting ‘new’ land will not be immediately or easily ‘habitable, liveable’.

- Are the two processes (desertification – thawing) proportional in time, or is one of them expected to occur first?

- No, they are not in proportion in time, and both are already well underway, but at different speeds and with different effects.

- Desertification is an ongoing, regional problem that already threatens the livelihoods of millions, and is progressing relatively rapidly in already arid areas. Its effects (crop failure, lack of drinking water) are immediate and immediate.

- Melting ice is also a continuous and accelerating phenomenon, but sea-level rise, the most dramatic consequence, takes centuries to fully unfold. Although glaciers are already retreating and polar ice caps are melting, the complete disappearance of huge ice masses and the resulting global sea-level rise of several metres is a longer-term scenario.

- No, they are not in proportion in time, and both are already well underway, but at different speeds and with different effects.

Summary

While both desertification and melting ice sheets are serious consequences of climate change, we cannot expect one process to somehow ‘offset’ the other. Desertification is exacerbating water scarcity in existing land areas and destroying arable land, while ice melt is threatening coastal areas primarily through sea-level rise and, in the long term, the water supply of glacier-dependent regions.

The key message is that we need to take immediate action against both processes by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to changing circumstances, for example by saving water.

What can we, as ordinary users, do?

What was it that American writer and civil rights activist Eldridge Cleaver said?

If you are not the solution, you are part of the problem.

This statement reflects the need for everyone to be actively involved in solving social problems, and passivity contributes to the current situation.

So, what can we do? How can we contribute, how can we be part of the solution?

Water saving tips for households

There are lots of solutions, and we’ll try to show you as many as we can, but in the meantime, here are some ideas that don’t cost any money, just a little attention! And what costs money, there are often community solutions! We’ll talk about those too.

In the bathroom

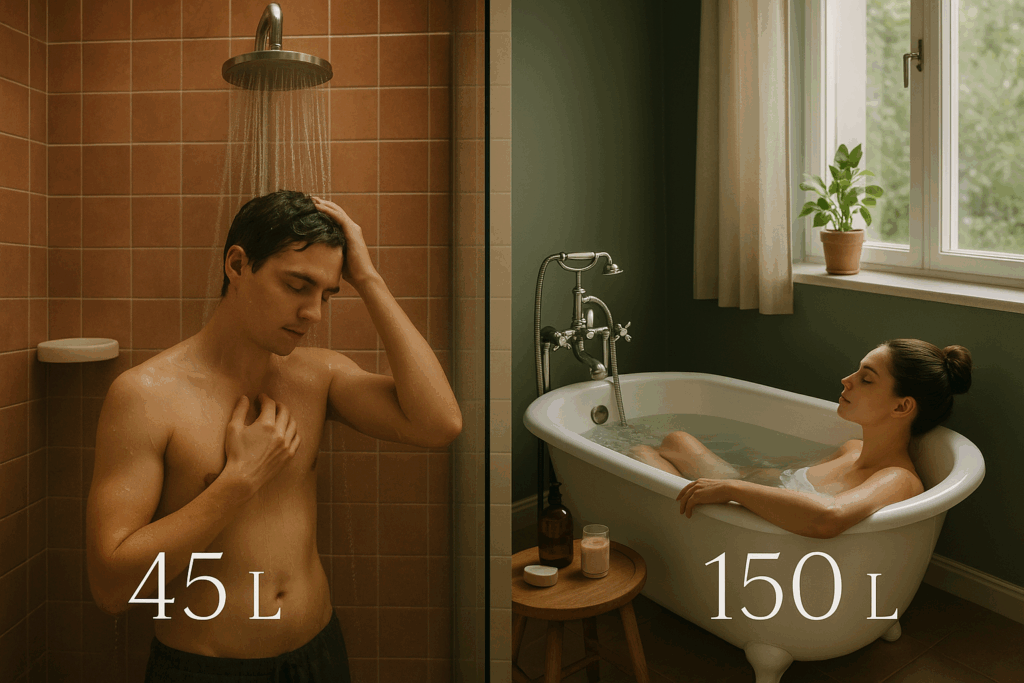

- By taking a shower, you can use as little as a third of the water you would use when bathing in a bathtub. Of course, the time of the shower and the type of shower head are not all the same! After all, an 8-10 minute shower with a traditional, older type of shower head can use up to 15-20 litres of water per minute, which is the same as 120-200 litres of water used in a bath.

So if you can, get a water-saving shower head! More modern shower nozzles tend to run at around 10-14 litres/minute, while truly water-efficient models can reduce consumption to less than 6-8 litres/minute, often by adding air to the water jet to maintain the feeling of pressure. So this alone can save 50-70%, meaning you only use half to one third of the water.

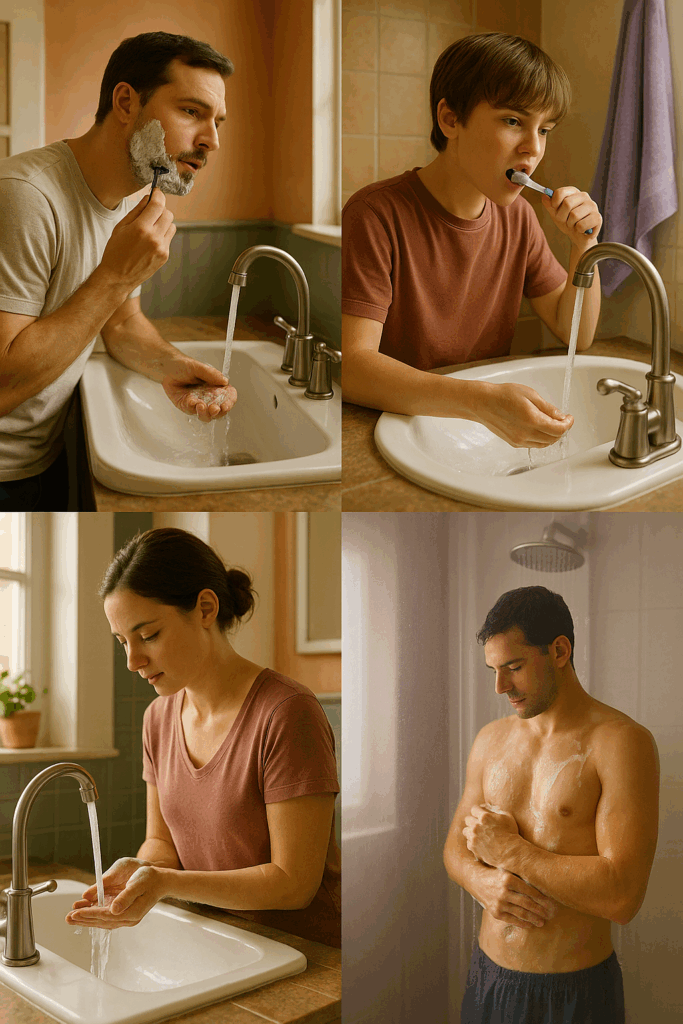

In fact! You can reduce water consumption even further by shutting off the water while shampooing and soaping so you don’t waste it! Of course, you can also get water-saving filters (percolators) for older shower heads, which will also help you reduce water consumption. And of course, you can drain all the water in the world if you don’t keep track of time.

- Turn off the tap when shaving and brushing your teeth, as well as when washing your hands and, as mentioned above, when showering while soaping yourself! It’s a small gesture, but it can save many litres of water a day. Only run the tap when you are actually using the water! It can save up to 10 litres of water per minute. Install a water-saving filter (percolator) on your taps, which mixes the water jet with air, reducing the amount of running water!

- And, surprisingly, an energy-efficient boiler (or efficient gas boiler, depending on how you produce hot water in your household) can also help reduce water consumption. After all, it heats water in less time (and keeps the heat on for longer) so you’ll be splashing out less while you wait.

- A constantly dripping tap can waste up to 15-20 litres of water a day. And a poorly sealed toilet tank can waste even more. Stop dripping taps and leaking toilet tanks as soon as possible! A constant drip can waste up to a bathtub’s worth of water in a month.

- Did you know that at least one third (33%) of all water used in a household is used for toilet purposes? Yes! Flush a third of your drinking water down the toilet. Of course, there are solutions to this too, for now let’s look at the toilet tank! When choosing a toilet tank, there are many options, from the use of grey water to the size of the tank, it’s worth doing some research. With an economical tank, you can reduce the amount of water used by up to a third. If you can, install a dual-function toilet tank! These allow you to flush smaller and larger volumes, so less water is wasted.

- Don’t use the toilet instead of the dustbin, never pour oil or food waste down it! On the one hand, they pollute the water, and on the other hand, by flushing the toilet and cleaning more water, we use unnecessary amounts of water.

- Collect water before showering. A practical solution is to collect the cold water in a bucket while you wait for the water to warm up for the shower. You can use this for watering plants, mopping or even flushing the toilet.

In the kitchen

- Do not wash the dishes with a continuous stream of water! You can either wash and rinse each piece individually (while the water flows over the other pieces in the sink tray underneath as you rinse, helping to dissolve the dirt in the unwashed pieces and using the same water more than once), or you can collect the dishes in the sink or in a bowl and wash them in the dishwashing liquid and rinse. While you are rubbing the dishwashing liquid over the sink, or while you are placing the already washed dishes, plates, glasses, cutlery on the drip tray, turn off the tap!

- Today’s dishwashers are already very energy and water efficient. They can save you a lot of time. If you don’t have a dishwasher, we don’t necessarily recommend getting one, but if you do, it’s worth using one, because modern dishwashers are much more water efficient than hand washing, especially if you only start them when they’re fully loaded.

- Do not thaw frozen food under running water! Take them out of the freezer the night before and put them in the fridge! By morning, they will have thawed enough for you to process. And if for some reason processing fails, the food is still safer in the fridge for a little later use.

More details

The ideal temperature in a normal refrigerator compartment is usually between +3°C and +5°C, most experts recommend +4°C. This is the range where food stays fresh and bacterial growth is minimal. In the freezer compartment, the optimum temperature is between -18°C and -22°C. Many fridges are set to -19°C by default, but -18°C is the most common recommendation for long-term food shelf life. So if you go by the recommended values, the temperature difference is 20-25°C, which is plenty for thawing.

- If you forgot to transfer or even take out frozen food in time, if you have a modern, energy-efficient microwave, you can use its defrost function – although we don’t like it. But it’s better to plan ahead, and definitely not to defrost in running water.

- In the same way, don’t use cold running water to cool your fruit or drinks in the summer heat!

In the laundry room

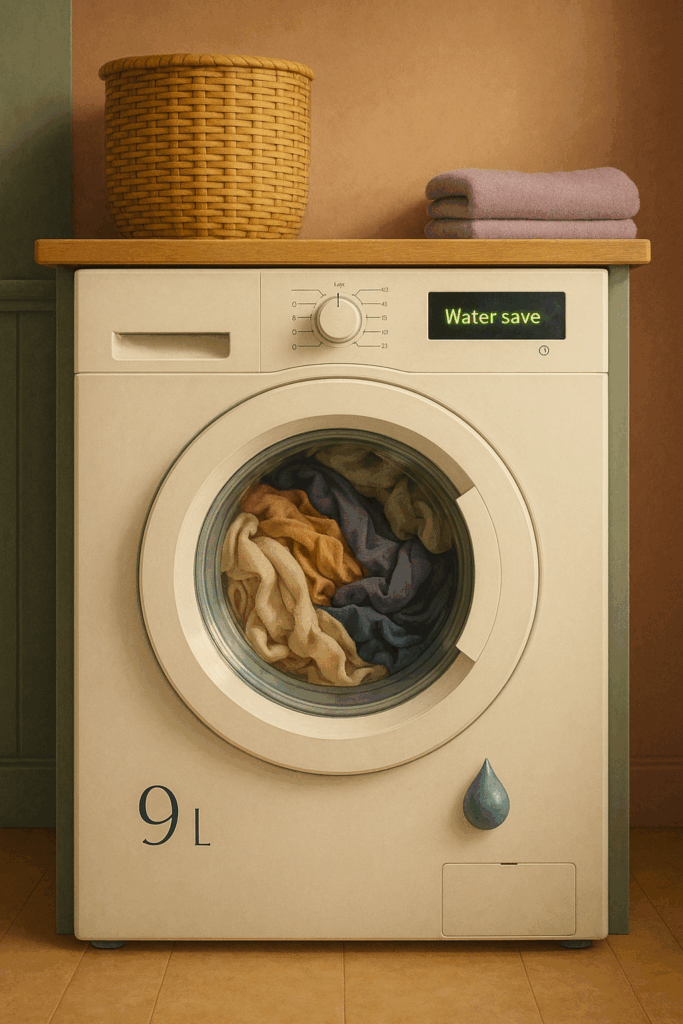

- Only start the washing machine when it is full! A half-empty washing machine uses the same amount of water as a full one.

- Use the washing machine’s energy-saving or short programmes. If your clothes are not too dirty, these programmes are perfectly adequate.

- It is worth using the “water-saving” programmes in the washing machine.

- Reduce the amount of chemicals used (cleaning products, cosmetics), as they all pollute our water!

In the garden and yard

- Collect the rainwater! Install rainwater collection tanks under the gutters. You can use this water to water your plants or even flush the toilet. This can seriously reduce your drinking water consumption. We’ll show you practical solutions for this later on. Rainwater harvesting is an old and simple practice, yet many aspects of it are neglected these days. In households, rapid drainage has taken over from water retention. Yet, for example, a roof of 100 square metres of surface area produces an average of 58 cubic metres of water per year, even in this climate, most of which can be collected if done properly.

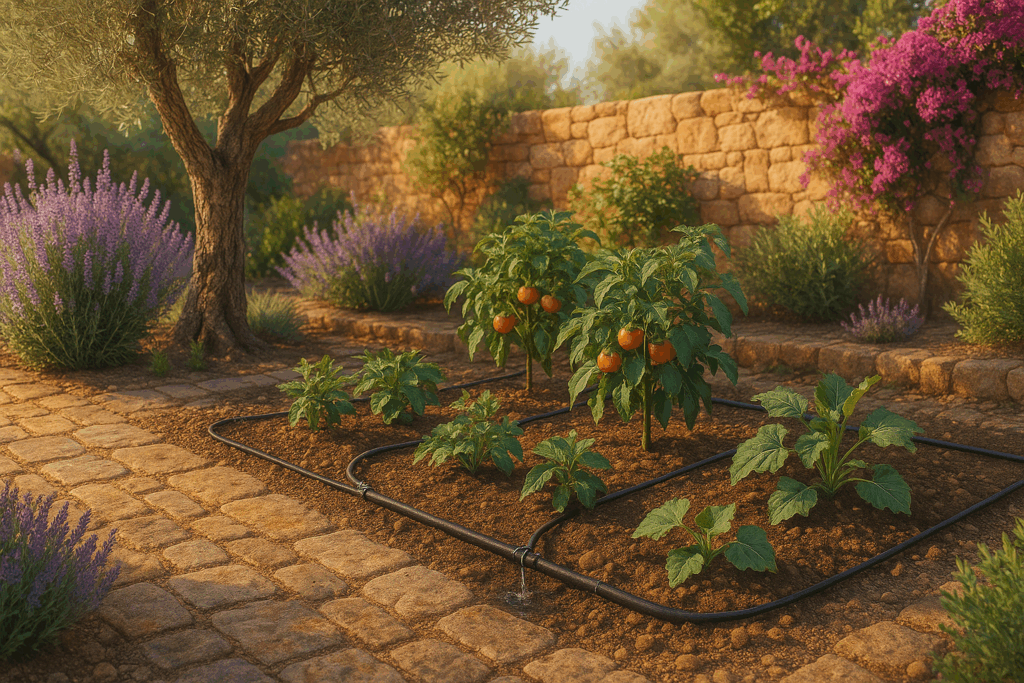

- Water wisely! It’s best to water in the early morning or late evening when evaporation is lower. Water less often, but water thoroughly so that the water gets deep .

- Cover the ground! Mulch (bark, wood chips, straw) helps to retain soil moisture, so less watering is needed. We will show you how to do this in our permaculture section.

- Use a drip irrigation system! This system delivers water directly to the roots of the plants, minimising evaporation loss.

- Choose drought-tolerant plants! In the long term, it makes sense to plant plants that are drought tolerant and require less watering.

- Stop watering the pavement and the road! Dust can be removed by sweeping.

- If you have a pool, cover it when you’re not using it! This will reduce evaporation and dirt, so you’ll need to fill or clean it less often.

Total savings potential – Summary

If all the above suggestions are followed consistently, total household water consumption can be reduced by between 32% and 68%!

This is a wide band, as the actual savings depend largely on it:

- the extent to which more frugal solutions can be introduced,

- the extent to which we can change our current water consumption patterns,

- what are the current conditions and habits in the household.

Of course, there are many more ideas that we can use to further increase our water savings. These are just a few examples. If you like it, please share it with others and we welcome your ideas and everyday practices!